1971 Unoffical World Cup

The little-known tournament that shattered records

The three most attended football matches this year so far? They’re all from the women’s game.

More than 91,000 fans packed into Camp Nou to watch Barcelona take on Real Madrid in the Champions League quarterfinals and Wolfsburg in the semis this spring. Just a few months later, 87,192 spectators filled Wembley to witness England win the Euros.

But a women’s match from five decades ago brought more people to the stadium than any recent record-breaking crowd in women’s football.

In 1971, at an unofficial World Cup in Mexico, 110,000 fans packed into a sold-out Azteca Stadium to watch Denmark take on the hosts in the final.

Denmark’s goalkeeper Birte Kjems remembers the crowd’s enthusiasm at the game. She told the Guardian, “When we walked out, the shouting and drumming was so loud that we couldn’t even hear each other when we tried to talk.”

But it wasn’t just the final that drew large crowds. Denmark’s first game drew around 40,000 with other games hovering closer to the six-digit mark.

Leah Caleb, England’s 13-year-old winger at the time said to BBC History, “You could feel in the weeks leading up to the games that something special was about to happen.”

It was fairly common for players to be in their early teens. As there were little to no opportunities to make a career in women’s football at the time, many had to quit the game when they had to support themselves.

“Everywhere we went there would be people coming up to us for our autographs. We had police escorts going to matches. Once, our coach was stopped on the highway because they all wanted to shake our hands through the window and give us things,” continued Leah.

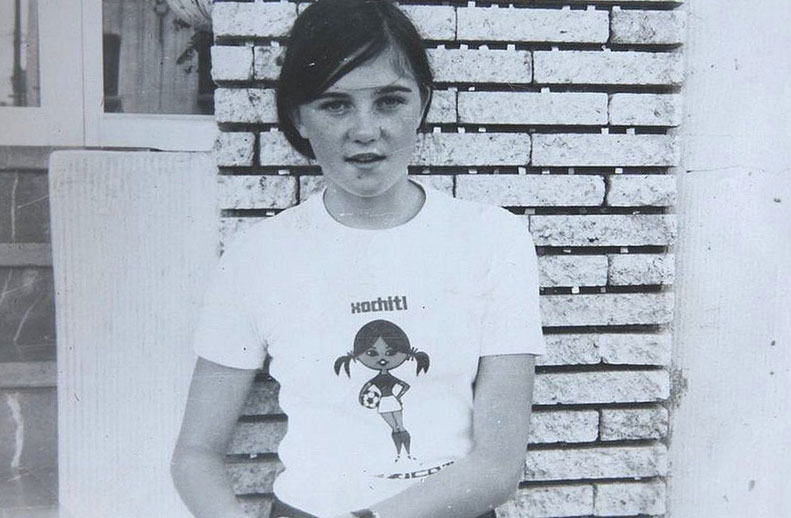

Leah Caleb wearing a shirt with Xochitl, the tournament's mascot on it. Xochitl is Nahuatl for 'flower.'

Although six teams competed at the unofficial World Cup - Mexico, Argentina, England, Denmark, France, and Italy - many women were barred from playing on home soil at the time and FIFA took until 1991 to host an official women’s World Cup, 61 years after the men’s inaugural competition.

In England, following a rise in women’s football during the First World War, the Football Association (FA) prohibited women from playing on FA pitches from 1921 until after the tournament in 1971. The FA cited the game as, “unsuitable for females and ought not to be encouraged,” as grounds for the ban.

In Brazil, the National Sports Council passed a ban on the women’s game in 1941 noting, “women will not be permitted to practise sports that are incompatible with the conditions of their nature.” It took until the women’s liberation movement of the 1970s for the ban to eventually be lifted in 1979 with the sport officially recognised by the National Sports Council in 1983.

These are just two of countless examples.

So how did the 1971 tournament garner massive crowds even by today’s standards during an international backdrop that not only largely dismissed the women’s game but disallowed it?

France team

Despite the women’s game being repressed, when it was given space to grow, it flourished.

Investors took note and from the onset, organisers saw the 1971 tournament as an opportunity.

A year prior, 50,000 spectators watched Denmark beat Italy 2-0 at Turin’s Stadio Olimpico Grande in the Martini Rosso Cup – what some consider to be the first women’s World Cup.

Later in 1970, 60,000 fans in Mexico watched their team take on Italy in the first of a series of friendlies showing again that women’s football could garner large crowds.

Following the success of their tournament in Italy, the drink company Martini Rosso sponsored every 1971 team, paying for their plane tickets, accommodation, and kits. Other international brands joined in too believing the tournament could create good advertisement opportunities with the large number of fans it might draw.

Word of the tournament got around Mexico through widespread press coverage and every Mexico match was broadcast on colour TV.

“There were a few snippets in the British press but it was a jokey type of thing,” recalled Gill Sayell, England’s winger who was 14 at the 1971 tournament, to BBC History.

“But in Mexico, we were chaperoned everywhere, taken to functions and we went on TV. For a schoolgirl, to be plucked into that limelight was quite surreal.”

It wasn’t just the England team experiencing mass media attention. Every team had been thrown into the spotlight for these few weeks.

Birte told the Guardian, “The atmosphere around the country was amazing. It was like, ‘we’ve had the Olympics and the men’s World Cup, now here come the women so let’s make a big party for them, too.’ It was quite a new world. There was something in the papers about women’s football every day and everywhere we went people wanted photographs and autographs. You could never just walk out to a shop because there were big crowds waiting for us around the hotel.”

Pink and white goalposts

Notably, much of the media coverage, particularly at the beginning of the games, and tournament advertisements downplayed players’ athleticism and focused on their physique and femininity instead.

A 1971 New York Times article covering the tournament titled, ‘Soccer Goes Sexy South of Border’, claimed the championship, “promises to be something of a mixture between a sports event and a beauty contest… the shorts will be as close as possible to hot pants.”

Goal posts were painted pink and white and alternative matches composed of actresses, singers, and girls in shorts dominated a lot of the press during the tournament’s early stages.

As the tournament progressed, media coverage shifted towards the game itself with reporters acknowledging the athleticism of the players.

During England’s match against Mexico, Gill told BBC History she remembers, “coming up the steps from the changing room, which was below the pitch, and the noise from the crowd was deafening.”

A reported 80,000 spectators filled the Azteca Stadium for that fixture which would put it in the top-five attended women’s matches in history.

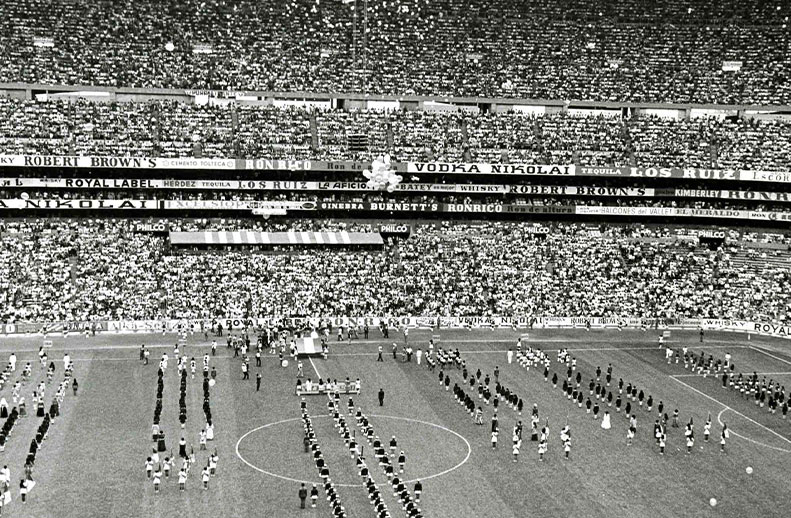

The final at the Azteca Stadium

The final, however, reportedly drew more fans to a women’s football match than any other game past or present.

A year after Brazil won the men’s World Cup at the Aztec Stadium in Mexico’s capital, a staggering 110,000 fans packed into the arena to watch Mexico take on Denmark.

Courtesy of a hat-trick from 15-year-old forward Susanne Augustesen, Denmark defeated Mexico 3-0.

And then Birte remembers something odd happening. In an unheard-of occurrence, Mexico fans rose to their feet to show respect for the quality of play from Denmark.

“After Susanne’s third goal we heard something very strange: applause from the home crowd. People told us afterwards that that was one of the first times they had heard fans in the Azteca applaud the opposition,” said Birte to the Guardian.

To celebrate, the Danes doused themselves in pink champagne. “I didn’t even know pink champagne existed, but there was lots of it after the final,” Birte exclaimed.

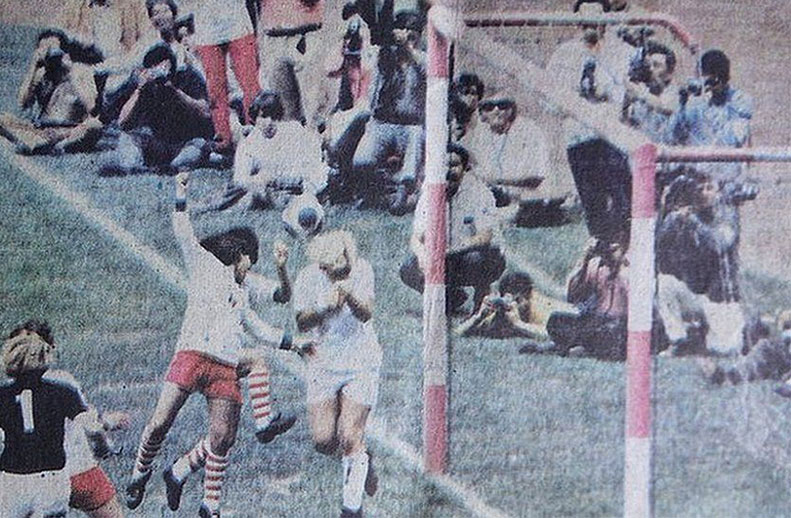

Susanne Ausustesen's first goal

Despite the swell of attention players experienced at the tournament, the enthusiasm didn’t follow them home. Upon returning to England, Gill noted to BBC History that she remembers, “From the high of Mexico, it was just back to normal. I found myself thinking, ‘did that actually happen?’ which is a shame. It would have been great if the women’s game had gone on from there but it just sort of went flat.”

For playing in the tournament, governing bodies in England gave every player a short ban and Harry Batt, the team’s coach, received a ban for life.

“I was very disappointed,” commented Gill. “You go from representing your country and then you can’t even play for your home team.”

When Denmark returned home, Birte told the Guardian, “Ordinary people were very excited but not the official men.

“On the day we landed the head of the DBU [Vilhelm Skousen] said there would never be women members of the Danish Football Union during his lifetime.”

However later that year, UEFA passed a motion prompting member states to recognise the women’s game which the DBU did in 1972. It wasn’t prioritised or promoted.

“I and other players lost some of our best football years because men insisted on doing things their way and weren’t quick enough about it,” said Kjems to the Guardian.

“So I think, even now, it is very important for women to stand up and do things for themselves. Don’t wait for men to do it for you.”

The 1971 tournament is one of the most vivid examples of the enthusiasm the women’s game can generate. It is, however, also one of the starkest examples that a record-breaking crowd does not guarantee sustained momentum or support.

As the football world comes off new women’s Champions League and Euros records, investment into the women’s game needs to continue for the game to keep growing. Women’s football is breaking the cycle of being just a big tournament sport.

With the women’s game on the rise, it’s up to everyone - from fans to brands to the press - to help maintain the current momentum and fight for an equal game.